Table of Contents

If you spend enough time reading about psychology, you will inevitably learn about the replication crisis and the debate whether psychology is a science. You must have heard some people say that it is soft-science at best, not a science at worst. You will usually hear it from the “enlightened” IFLS type of people who believe science to be this absolute monolith, whose results may not be influenced by extrinsic factors (like politics, economy, funding) as it follows a very rigorous method. Their main point is that natural sciences are objective, unbiased, because they are based on hard data that mostly speaks for itself, you just have to come up with the right experiment. In this scenario, psychology and the humanities, in more general, with their more discursive method and more overt incorporation of philosophy are juxtaposed with natural sciences like chemistry, physics, biology, with their heavy use of quantitative tools like mathematics, that are seemingly not subject to interpretation and cannot be manipulated.

For some psychologists question “is psychology a science?” will be a question of credibility, as they will see science as the arbiter of truth and anything that falls outside the scientific method is not knowledge. To be included in the realm of science means to be able to discover, instead of merely construct or discuss.

Philosophy of science

Today I want to reverse this argument, as I believe neither humanities nor the natural sciences tightly fit into this idealistic picture of how science works. Neither the humanities nor medicine research, in this case, work within a vacuum. Both are subject to bias and require interpretation. Both struggle with the replication crisis. The main differing factor is that one is more open about its relation with philosophy (psychology), the other one less so (medicine). This distinction has become even more blurred due to the advent of the biopsychosocial model of disease into medicine. In fact, a very convenient manoeuvre has been performed by the discipline of neurogastroenterology. It borrowed some tools from psychology — namely hypnotherapy. These tools naturally carry with them large chunks of philosophy that lend basis to their use. Once those tools have been assimilated by a discipline that is by and large considered a “hard” science — neurogastroenterology — suddenly proposing the basis of how this is actually supposed to work becomes less important than producing some figures, fMRI pictures and the like. So, we have this Trojan Horse in the form of the biopsychosocial model with all its philosophical implications suddenly becoming a large part of the mainstream science, with very little scrutiny.

Let’s take a closer look at gut-directed hypnotherapy in this context.

Dipesh H. Vasant and Peter J. Whorwell — its main proponent — describe it as follows:

Clinical hypnosis is a verbal intervention that utilizes a special mental state of enhanced receptivity to suggestion, to facilitate therapeutic psychological and physiological changes. Broadly, the aims of gut-focused hypnotherapy are to induce a deep state of relaxation to guide the patient to learn how to control their gut function. […] During subsequent hypnotherapy sessions, the patient is taught a series of approaches to enable them to gain control of their gut function. The approach is adapted to the patients’ symptom profile and own personal imagery using metaphors. For example, patients with a functional bowel disorder could be asked to imagine their gut as a river and modify its flow according to their needs depending on whether they have predominant diarrhea or constipation. For abdominal pain, the tactile approach of the patient placing their hand on their abdomen, feeling warmth, and using this to alleviate pain can be useful. Similarly, an inflated balloon being slowly deflated can be used as a metaphor to reduce abdominal bloating. This is also sometimes combined with other helpful techniques such as teaching the patient diaphragmatic breathing.1

It is very hard to ignore that an intervention like this is based on many implicit philosophical presuppositions. The need for the state of hypnosis suggests that the same effects cannot be achieved by addressing the patient directly, in their basic state of consciousness. Therefore, to use hypnotherapy in relation to bodily symptoms, one has to accept that there is some other cognitive agent “at a deeper level” — you may call it psyche, the unconscious, brain, autonomic system depending on your inclinations — to whom one may appeal with different mantras and visualisations, AND who will also be able to take control over the autonomic bodily functions and alter them. To appeal to such an agent, we must accept that it has a linguistic structure, so it is able to understand those mantras and translate them into appropriate autonomic output to reduce bodily symptoms. To use visualisations, like the ones above (e.g. a knife signifying stabbing you feel in your bowels), some understanding of metonymy would be required.

This is surprisingly close to how Jacques Lacan, quite an esoteric mid-XX century French psychoanalyst, understood the Subject, and more specifically — the unconscious. One of Lacan’s most important points has been that “The unconscious is structured like a language” — in that it operates through signs, metonymy, metaphors, like language does.2

Mechanism of action

As mentioned before, similarly to some psychoanalysts, Whorwell suggests that this structure is able to modulate various autonomic functions:

While the exact mechanisms of gut-focused hypnotherapy in functional FGIDs are not fully understood, a number of studies have demonstrated its ability to induce changes in gastrointestinal function and physiology. For example, in the upper gastrointestinal tract, hypnotherapy has been shown to be able to modulate gastric acid secretion, accelerate gastric emptying, and alter orocecal transit time measured using the lactulose hydrogen breath test, in controlled studies in healthy participants. Similarly, in the lower gastrointestinal tract, some studies conducted in patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) have shown appreciable differences in colonic sensory and motor function before and immediately after hypnotherapy, demonstrating modulation of postprandial gastrocolic reflex activity, colonic motility, and visceral hypersensitivity. In an interesting study of the effects of hypnotherapy on gastrointestinal motility in a heterogeneous group of IBS patients, Lindfors et al did not detect any significant long-term differences in gastric emptying, small intestinal transit time, antroduodenal manometry or colonic transit time before and after hypnotherapy. However, the inclusion of patients with both constipation and diarrhea predominant IBS in this study makes the motility and transit data difficult to interpret, given the differing therapeutic approaches to gut-focused hypnotherapy between the two IBS subtypes and the potential opposing effects on these metrics that the differing approaches to hypnotherapy may have.

It is interesting to see how he downplays studies that do not fit his own views. He uncritically accepts (often his own) studies of: fifteen3, twenty-three4, six,5 twenty-six,6 twenty-eight,7 seventeen8 people; but goes into a digression to dismiss conflicting results of a randomized-controlled trial of eighty-one people.9 Nothing wrong with critique, of course, but this seems to be rather one-sided.

How does PJ Whorwell explain the mechanism of hypnotherapy?

As alluded to earlier, while the exact mechanisms of action of gut-focused hypnotherapy remain unclear, a number of studies using functional brain imaging techniques have given some plausible explanations which suggest that hypnotherapy can induce changes in neuroplasticity. For example, several studies have investigated brain activity in response to painful visceral stimuli in IBS. Based on this work, and other studies, current understanding is that patients with painful FGIDs have abnormal signaling in visceral afferent pathways and central pain amplification. Interestingly, the anterior cingulate cortex, one of the brain regions most consistently enhanced by painful visceral stimuli in IBS, has been shown to be an area which can be modulated by hypnotherapy during treatment focused on altering the response to a noxious painful stimulus (Figure 2). Studies of hypnotherapy in the chronic pain literature have shown that hypnotic suggestions for pain modulation also impact the prefrontal, insular, and somatosensory regions, and there is evidence for differing brain activations depending on whether the hypnotic suggestion is related to pain affect or pain intensity. Moreover, a recent, well-designed, controlled study has shown that responders to hypnotherapy with moderate to severe IBS had attenuation of brain activity in the posterior insula and that improvement in symptoms was associated with normalization of evoked brain responses to painful visceral stimuli (Figure 3). These data suggest that the use of gut-focused metaphors, hypnotic suggestions for physiological improvement, and imagery used during hypnotherapy, may select specific related peripheral and central gut-brain neuronal pathways, leading to favorable neuroplastic changes induced by practice and further re-enforcement during, and in between hypnotherapy sessions. This would perhaps explain the functional, physiological and clinically relevant benefits that have been observed following hypnotherapy, which may drive such neuroplastic changes to restore ‘normal’ processing of painful visceral stimuli in patients with FGIDs.

The problems with this report are manifold. The first is that invoking neuroplasticity does not explain the mechanism of action at all. Neuroplasticity is just an innate property of the brain that does not explain anything on its own, in this context it is just a convenient neuroscientific buzzword, for lack of a better explanation. We know that neural networks may rearrange, but we want to know how this rearrangement comes about.

Elucidating the mechanism of action in this case would require explaining how mantras/imagery delivered to the patient translate into altering brain function (especially as applied to autonomic processes that are not supposed to be under the “user’s” control) that leads to pain reduction. Why specifically mantras/imagery, and not something else, and why these specific ones are needed to elicit those changes.

This is all too similar to the hard problem of consciousness, but in a somewhat opposite direction. In Whorwell’s defence, I doubt we will ever find satisfying answers to questions of this kind.

Does it work?

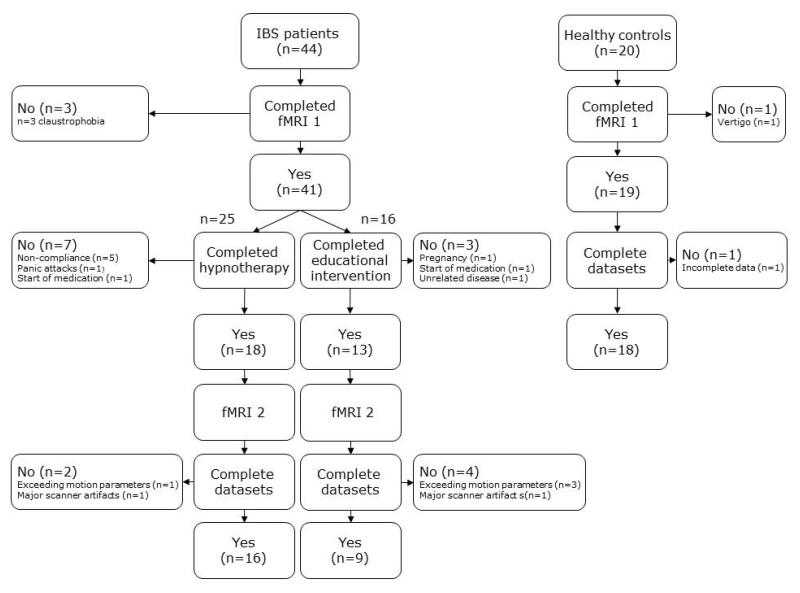

Next, let’s look at the study that PJ Whorwell calls well-designed:

What instantly stands out is that there was no subgroup of healthy controls that received hypnotherapy. This only leaves you wondering whether healthy controls have similar decrease in brain activity in those pain-related regions, just from a lower baseline, and what it means. Is there any change? Does their pain threshold increase even higher? Does their pain threshold not change despite change in brain activity? What does this mean? How important is the change in brain activity in this context?

Aside from this, it is not clear whether deep relaxation or hypnosis alone, would be enough to produce similar findings on fMRI. So, healthy people and people with IBS entering a state of deep relaxation or hypnosis, but without all the imagery and mantras would be another two control groups worth considering.

The next issue is that modulation of activity of brain regions associated with pain during hypnotherapy does not explain its efficacy past the testing period. Meaning that it might be expected to see attenuation in some brain activity in a state of deep relaxation/hypnosis, but ascribing significance to these findings past the testing period is overinflating the conclusions.

It does look like the authors of the study are at least aware of this problem:

Long-term treatment follow-up studies with brain imaging evaluation are needed to evaluate if brain response alterations persist, and if this therapy may be curative for selected patients.

The main problem that has haunted hypnosis studies for as long as they existed is that sham-controlled studies are extremely difficult. Tricking people into believing they are undergoing the “true” hypnosis while being subjected to a placebo might not be possible. So, if they can’t be effectively blinded, a direct comparison that would once and for all prove that hypnotherapy is more effective than placebo, ergo is not just a purple-hat placebo, is not possible.

In fact, placebo visceral analgesia works, as evidenced by the study below10, and has strikingly similar neural correlates to the ones found in hypnosis studies invoked by Whorwell:

To manipulate the expectation of analgesia, participants were informed that they would receive an intravenous infusion containing either a highly potent analgesic drug (100% expectation); possibly the analgesic drug or placebo because administration was being accomplished in a double-blind fashion (50% expectation), or an inert substance, i.e., sodium chloride (0% expectation). In reality, participants received sodium chloride (intravenous drip) in all 3 conditions (for more details, see also Placebo Instructions and Procedures). […] Within responders, pain reduction correlated with reduced activation of dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortices, somatosensory cortex, and thalamus during cued anticipation (paired t tests on the contrast 0% > 100%); during painful stimulation, pain reduction correlated with reduced activation of the thalamus. Compared with nonresponders, responders demonstrated greater placebo-induced decreases in activation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during anticipation and in somatosensory cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and thalamus during pain. In conclusion, the expectation of pain relief can substantially change perceived painfulness of visceral stimuli, which is associated with activity changes in the thalamus, prefrontal, and somatosensory cortices.

This suggests that the pain relief effects are setting-dependent. Which is in line with observations made by Whorwell:

Another challenge facing tertiary services is that the outcomes for gut-focused hypnosis appear to be better in highly specialized research centers rather than in smaller community settings. The exact reasons for these differences are unclear but may be due to differences in the training of therapists.11

It is interesting that he reaches completely different conclusions. He conveniently glances over the fact that the environment in which the therapy is delivered sets expectations, which might influence the size of the effect of pain reduction. One could almost think of an experiment where you have two groups. One group gets referred for hypnotherapy to a large and modern tertiary-care centre by a professor with a 40-year tenure, such as Whorwell, who has explained to the patient that they will undergo a highly-effective, scientifically proven treatment, as he probably normally does anyway. The second group gets referred for hypnotherapy to a small local centre by their GP who explained multiple real designs flaws of hypnotherapy research and concedes it is seen as controversial. Then exactly the same hypnotherapists deliver the same treatment to both groups. One may imagine the results could be quite different.

There is little doubt that a lot of people benefit from this intervention and this is not the point I am trying to dispute here. Some main points are that there are many facets of this treatment that escape the scientific method and are just unfalsifiable. Pretending that it is a treatment modality, 100% relying on science, with no elements of philosophy, whose efficacy has been proven beyond any doubt is harmful to the patients. It reinforces the view that “brain” of the patients with gut disorders is their main problem, no matter the etiology of their particular case of this very heterogenous condition. It requires everyone to a priori accept the notion that the severity of patients’ symptoms can be negotiated with their brain by “talking” with it, by using different metaphors, metonymies, mantras, should they wish. It is easy to get an impression that this very much resembles older psychosomatic theories of IBS, just using more neuroscientifically sounding descriptions and tools such as fMRI, typically associated with “hard” science.

Footnotes:

- Vasant DH, Whorwell PJ. Gut-focused hypnotherapy for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Evidence-base, practical aspects, and the Manchester Protocol. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019; 31:e13573. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13573 ↩︎

- You can read about it in a various places, like here or here, but I must warn you that Lacan’s writing is very dense and esoteric, even when you read the secondary sources. ↩︎

- Prior A, Colgan SM, Whorwell PJ

Changes in rectal sensitivity after hypnotherapy in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

Gut 1990;31:896-898. ↩︎ - Lea, R., Houghton, L.A., Calvert, E.L., Larder, S., Gonsalkorale, W.M., Whelan, V., Randles, J., Cooper, P., Cruickshanks, P., Miller, V. and Whorwell, P.J. (2003), Gut-focused hypnotherapy normalizes disordered rectal sensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 17: 635-642. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01486.x ↩︎

- Beaugerie L, Burger AJ, Cadranel JF, et al

Modulation of orocaecal transit time by hypnosis.

Gut 1991;32:393-394. ↩︎ - CHIARIONI, G., VANTINI, I., DE IORIO, F. and BENINI, L. (2006), Prokinetic effect of gut-oriented hypnosis on gastric emptying. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 23: 1241-1249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02881.x ↩︎

- Kenneth B. Klein, David Spiegel,

Modulation of gastric acid secretion by hypnosis,

Gastroenterology,

Volume 96, Issue 6,

1989,

Pages 1383-1387,

ISSN 0016-5085,

https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(89)90502-7. ↩︎ - Kenneth B. Klein, David Spiegel,

Modulation of gastric acid secretion by hypnosis,

Gastroenterology,

Volume 96, Issue 6,

1989,

Pages 1383-1387,

ISSN 0016-5085,

https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(89)90502-7. ↩︎ - Lindfors, P., Törnblom, H., Sadik, R., Björnsson, E. S., Abrahamsson, H., & Simrén, M. (2012). Effects on gastrointestinal transit and antroduodenojejunal manometry after gut-directed hypnotherapy in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 47(12), 1480–1487. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365521.2012.733955

↩︎ - Sigrid Elsenbruch, Vassilios Kotsis, Sven Benson, Christina Rosenberger, Daniel Reidick, Manfred Schedlowski, Ulrike Bingel, Nina Theysohn, Michael Forsting, Elke R. Gizewski,

Neural mechanisms mediating the effects of expectation in visceral placebo analgesia: An fMRI study in healthy placebo responders and nonresponders,

PAIN, Volume 153, Issue 2, 2012, Pages 382-390, ISSN 0304-3959,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.10.036. ↩︎ - Vasant DH, Whorwell PJ. Gut-focused hypnotherapy for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Evidence-base, practical aspects, and the Manchester Protocol. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019; 31:e13573. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13573 ↩︎